用户:洛零/sandbox/Pelagic Ecosystems/Killer whales

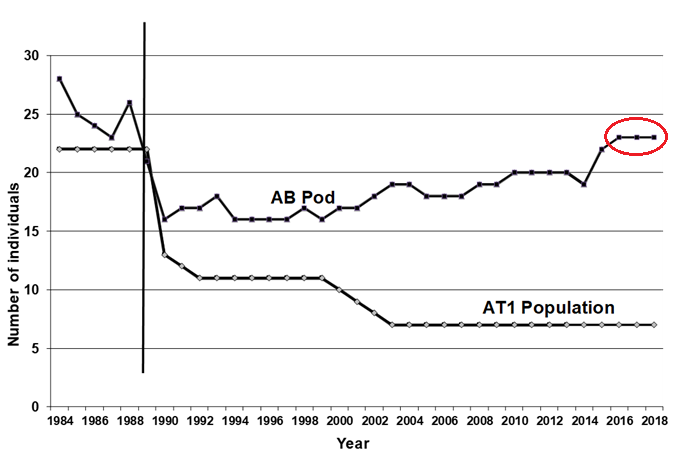

KILLER WHALES HAVE GENETICALLY AND BEHAVIORALLY DIFFERENT GROUPS, CALLED ECOTYPES. BOTH RESIDENT ECOTYPE (AB POD) AND TRANSIENT ECOTYPE (AT1 POPULATION, SHOWN IN THIS PHOTO) KILLER WHALES DIED FOLLOWING THE EXXON VALDEZ OIL SPILL IN 1989. AB POD IS RECOVERING AFTER 30 YEARS BUT HAS STILL NOT REACHED PRE-SPILL NUMBERS. THE AT1 POPULATION IS NOT RECOVERING AND MAY BE HEADED TOWARD EXTINCTION.

Why are we sampling? We are monitoring population recovery in both the resident killer whale ecotype (the AB pod) and the transient ecotype (the AT1 population), both of which suffered a significant number of deaths following the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. These two killer whale ecotypes are separated based largely on genetics and diet preference—resident killer whales primarily eat fish while transient killer whales prefer marine mammals—and, despite the transient moniker, both groups are found regularly within the Prince William Sound and Kenai Fjords study area year round.

As an apex predator, killer whales play a key role in the ecosystem through predation on fish and marine mammals. They are also a primary wildlife species of interest for viewing by the region’s vibrant tour boat industry. The tour boats provide not only a broad audience for the dissemination of our findings, but an opportunity to stress the importance of viewing guidelines and considerate behavior around the whales.

What are we finding? The fish-eating AB pod has made substantial steps toward recovery after 30 years but surprisingly has still not reached pre-spill numbers and in recent years there is indication that its growth may have paused. The marine mammal-eating AT1 population is not recovering and may be headed toward extinction, although its numbers have remained at 7 individuals for over a decade. This project has determined that killer whales are sensitive to perturbations such as oil spills but has not yet determined the long-term consequence (which may include extinction) or the recovery period required. As an apex predator, this species (both fish and mammal eating types) has an important role in the ecosystem. Additionally, they are a primary focus of viewing by an expanding tour boat industry in the region. Catalogs of individuals provided by this project are used by tour boats to enhance viewer experience along with direct interaction with the research vessel in the field. The draw of the whales and the interest in the research program fosters understanding and appreciation of the local environment and fauna by both visitors and residents.

Unlike many cetaceans, killer whale populations can be closely monitored, down to the individual in some cases, which allows development of a detailed and comprehensive population dynamics model for the fish eating residents. (Matkin et al. 2014).

The remaining members of the very localized AT1 (Chugach) transient population are annually monitored and each individual observed and cataloged. The wide-ranging Gulf of Alaska transients , also mammal eaters, are photographed when possible to determine trends in numbers. Also, all photographic identification data for the offshore form of killer whale are contributed to a coast-wide database at the Pacific Biological Station (Nanaimo, BC, Canada).

This project is a unique opportunity to continue a comprehensive monitoring program for a keystone marine species with three ecotypes and multiple populations. This project was initiated in the early 1980s which provides an exceptional data lens for evaluating trends in population and monitoring other changes. Our close collaboration with similar long term projects in Puget Sound and British Columbia links our work closely with research on the endangered Southern residents of Puget Sound and Washington State.

NUMBER OF WHALES IN AB POD AND AT1 POPULATION BY YEAR. NOTE: PAST THREE YEARS TOTAL FOR AB POD (CIRCLED) DOES NOT TAKE INTO ACCOUNT THREE MISSING MATRILINES (AB17, AB22, AND AB14).

We have observed an increasing tendency toward temporary (and in some cases permanent) splitting of pods. This may signify more challenging feeding opportunities (e.g., fewer numbers of fish/smaller school size) that favor hunting in smaller groups. A similar trend has been observed in British Columbia. In recent decades, the southern Alaska resident killer whale population (except for AB pod) has grown steadily. This trend may be changing. In 2018, of the 148 killer whales in 18 matrilines in our core pods that were photographed, only two calves were recruited and there were three apparent new mortalities. In 2017, for the 155 whales from our core groups that were photographed, there were four calves recruited and 8 mortalities (confirmed in 2018). A trend of zero or negative growth may be developing in the southern Alaska killer whale population.

Growth in the British Columbia northern resident population has halted in recent years and a similar situation may be developing in southern Alaska. There has been a rebound in salmon stocks in the past 40 years that we suspect has fueled increases in numbers in most resident pods in recent decades but this response may have ended and recent declines in north Pacific Chinook salmon may be having an impact.